If you have been following this series of CODE Framework articles, you are already aware that CODE Framework provides developers the ability to use, create, and customize awesome looking WPF application themes that also make apps more maintainable and easier to build. But not everyone wants to create brand new Themes or customize existing ones. Instead, why not just use one of the great themes that ship out of the box?

In past articles, we have presented various features offered by CODE Framework, and in doing so, we have usually applied a default theme, such as the Metro or Workplace themes, without giving much explanation as to which themes are available. In fact, in one article, I have even discussed creating custom themes from scratch, which is probably easier than you would think. Still, most people just want to take advantage of what is already there.

Themes in CODE Framework are always evolving. When the framework originally shipped, it only shipped with 2 or 3 themes that were meant as starting points for developers to create their own. However, feedback received from the developer community has quickly made it clear that people simply wanted to use ready-to-go themes. After all, creating what is often considered "eye-candy" is not what developers are usually good at or enjoy. For this reason, we have made theme creation a high priority in the development of the framework, and we will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. With that in mind, this article is meant to be seen as a "taking inventory" type of article, showing the themes that are available as of spring 2013. Make sure to check back for even more new themes.

What Are Themes?

Before we can really dive into an exploration of the standard themes, it is worth discussing what themes in CODE Framework are. Often, users as well as developers think of "themes" or "skins" as the ability to change the appearance of an application, mainly by switching colors. I am writing this article in Microsoft Word, and I can switch the color themes of Word in the options menu. Similarly, it is possible to switch the color theme of Visual Studio 2012.

While it isn’t completely wrong to think along these same lines in CODE Framework, it would not do the CODE Framework theming feature justice. Switching simple colors is usually a matter of swapping out color resources while leaving the rest of the application alone. This is certainly something CODE Framework supports, but it pales in comparison to the "serious" theme switching capabilities provided by the framework.

In CODE Framework, themes switch the fundamental make-up of an application. Does your application use a Ribbon, a drop down menu, tiles, or a completely different approach to navigation? Does your app open multiple windows, or are new views simply opened inside the main window, perhaps inside a tab control or something similar? Themes drive the arrangement and layout of screen such as data edit forms (which also has the advantage that instead of hand-coding screen layouts, you have the optional ability to let a theme handle the switch the fundamental make-up of an application. Does your application use a Ribbon, a drop down menu, tiles, or a completely different approach to navigation? Does your app open multiple windows, or are new views simply opened inside the main window, perhaps inside a tab control or something similar? Themes drive the arrangement and layout of screen such as data edit forms (which also has the advantage that instead of hand-coding screen layouts, you have the optional ability to let a theme handle the nittynitty gritty of that task). Themes change how items are displayed in lists and grids. Themes change the look of status updates, notifications, and message boxes. Themes may change art assets such as standardized icons. The list goes on and on.

Different application have different requirements for themes. Some application want to switch themes on the fly. Sometimes, the switch may be as simple as changing colors and fonts, while sometimes developers want the user to have the option to switch between a menu and a Ribbon approach. Or perhaps the application is meant to be a desktop application using an Office-style user interface, but when the user wants to use the app on a slate with touch support, the application switches into a modern Windows 8 style ("Metro") design completely on the fly.

Switch your app from a desktop app to a touch enabled slate application simply by swapping themes!

Other developers simply pick one theme and run with it. They may not be interested in switching themes on the fly, but each application needs some kind of consistent look, right? Not to mention that some of the automated features provided by the theming engine simply make development easier and faster as the theme handles many difficult tasks. And who knows? Maybe a few years down the road the chosen look isn’t perceived as particularly modern anymore, at which point a theme switch should be easy and not require a major re-write of the application.

You probably are starting to get the idea: CODE Framework themes are super-powerful and do a lot! More than I can discuss in this article, in fact. I encourage you to take a look at other articles in this series to see some of the fancier theme features at work.

A Sample Application

To demonstrate the different themes, I have created a small sample application. You can download it as an attachment for this article or from To demonstrate the different themes, I have created a small sample application. You can download it as an attachment for this article or from . The sample provides a small version of a magazine management application (after all that is a scenario I am very familiar with as the publisher of CODE Magazine). The application can show a list of subscribers and allows editing of individual subscriber records. It also shows a list of magazines with the ability to print that list (using the CODE Framework document engine). All the data is locally created in the sample (sometimes randomly) so you can run it without having to set up a database or worry about any other external dependencies.

The overall setup of the application is entirely based on the default CODE Framework WPF application template. (If you do not have these templates installed, see the sidebar for more information on how to download these tools). When creating a new CODE Framework WPF application you can choose which themes you would like to include in a wizard. To follow along with my example here, simply accept the defaults to get all the standard themes.

To implement the specific examples, I have created a few very small view models (many based on the examples, I have created a few very small view models (many based on the StandardViewModelStandardViewModel class provided by CODE Framework, which makes view model creation a snap, wherever the standard models are applicable… typically in lists, such as the results of search screens). I have created matching views for each view model. As you look at the code in the views, you will discover only a handful of lines of code in the XAML files. Usually around 20 or so. I was able to heavily leverage the themed (think "standard models are applicable… typically in lists, such as the results of search screens). I have created matching views for each view model. As you look at the code in the views, you will discover only a handful of lines of code in the XAML files. Usually around 20 or so. I was able to heavily leverage the themed (think "templatedd") layout helper features of the framework and did not have a need to hand-code any of the UI layouts (although I could have certainly chosen to do so if a scenario would have required it).

I encourage you to take a look at the example code and explore the view models and the views, mainly to see how little code there really is.

As you explore the different themes of the application, you can either switch the themes on the fly (check under "View" such as the "View" menu or the "View" Ribbon tab, depending on the theme you are running) or you can change the name of the startup theme in As you explore the different themes of the application, you can either switch the themes on the fly (check under "View" such as the "View" menu or the "View" Ribbon tab, depending on the theme you are running) or you can change the name of the startup theme in App.xamlApp.xaml.

Using theme features not just creates professional looking apps, but it also improves developer productivity.

It is very important to understand that for all the examples shown in this article, no code changes are required when switching between themes. When looking at screen shots, it may often seem that the app has changed completely, to a point where one suspects it must be based on different code, but that is not the case.

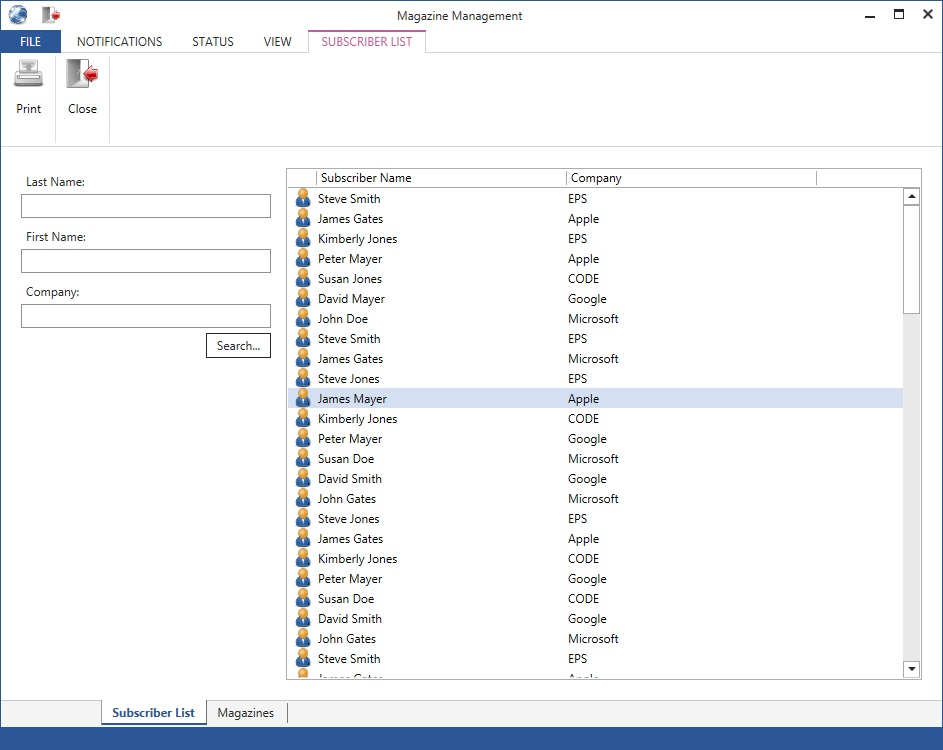

Battleship: The Mother of All Themes

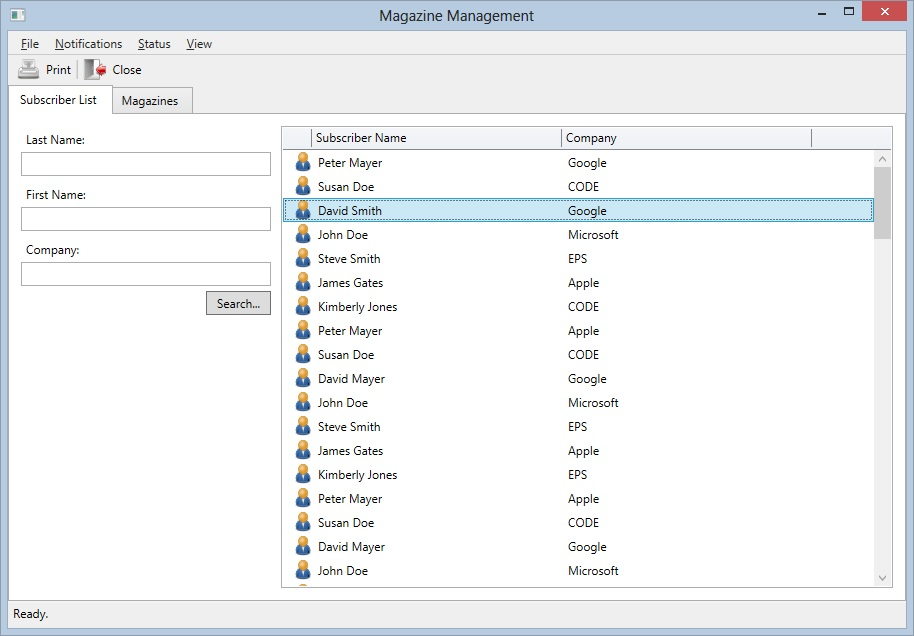

The most logical place to start exploring CODE Framework themes is the "Battleship" theme, named in (dubious) honor of "battleship-gray applications" typically built in Windows 95 and immediate successor operating systems. (Note: While this theme by default uses quit a few different shades of gray, you are free to customize the colors completely). These are the applications that have a toolbar and a menu across the top, a status bar at the bottom, content in between, and usually secondary windows that pop up when the user takes action. Figure 1 shows our sample application running in Battleship theme, with the subscriber search view open.

There are a few interesting things of note in the screen shot shown in Figure 1. As you can see, the main application window features a toolbar and a menu. The items in these elements are not put there manually, but instead, the theme picks those up from the views and view models that are currently open. The main window for instance shows all "Actions" defined by the subscriber list’s view model. (View models in CODE Framework can have an Actions collection… for more information, see the article on building WPF applications with CODE Framework). In addition, there always is an application-wide view model called the "start view model" (sometimes also referred to as a "global" view model), which launches as soon as the application starts (created by the home controller). The menu in Battleship actually consolidates actions from the start view model and the local view model to create a single unified menu. Top level menus (File, Notifications, Status, view models that are currently open. The main window for instance shows all "Actions" defined by the subscriber list’s view model. (View models in CODE Framework can have an Actions collection… for more information, see the article on building WPF applications with CODE Framework). In addition, there always is an application-wide view model called the "start view model" (sometimes also referred to as a "global" view model), which launches as soon as the application starts (created by the home controller). The menu in Battleship actually consolidates actions from the start view model and the local view model to create a single unified menu. Top level menus (File, Notifications, Status, ViewView) are driven by categories assigned to each action. If an action has multiple assigned categories, Battleship creates sub-menus. Using this setup, a standard menu structure can be created. (Additionally, following a standard CODE Framework pattern, each action could optionally define its own custom view in which case each menu item can show a full-blown WPF interface… but a detailed exploration of that technique is beyond the scope of this article).

The toolbar follows a similar pattern. It also consolidates the actions from the local and the global view models. However, in order to keep the toolbars to a manageable size, not all actions are shown in the toolbar. Instead, Battleship chooses to only use global actions of high significance (actions have a Significance property that allows defining 5 levels of importance) and local actions as long as they are above lowest significance. All view actions with highest significance show both an icon (if available) as well as a label. View actions with lower significance only show an icon (and in absence of an icon they only show the text).

You probably also noticed the status bar at the bottom (with a "Ready." status). In fact, I have created several example menu items for you to trigger different status updates and see the result in each theme. In Battleship, the status bar is relatively simple. It always shows the status in black on gray. (Note however that status bars can also host entire custom views in which case you are free to use fancy colors and images and whatever other UI features you want… I do however recommend to be careful putting interactive controls like textboxes into the status bar). The Battleship status bar is always there, regardless of whether there is any status text to show or not.

Themes can be switched on the fly or they can be changed over time to keep an application’s look modern and fresh.

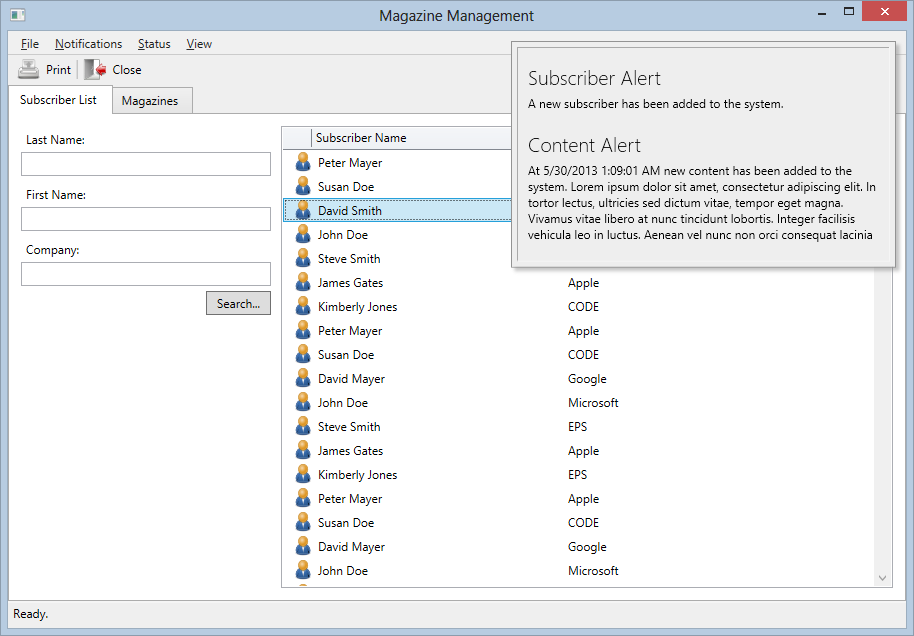

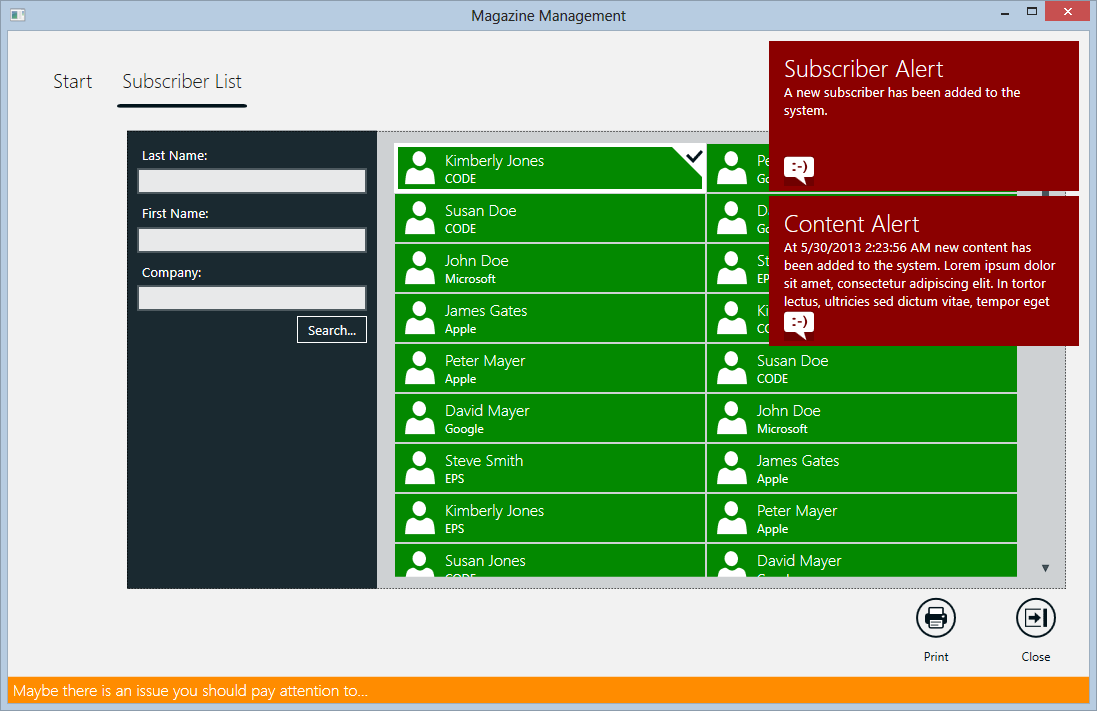

Another feature all CODE Framework themes support is "Notifications". This feature allows the developer to notify the user of some item of importance. (This is similar to Outlook showing you a notification "toast" whenever a new message arrives). Figure 2 shows the Battleship notifications in action. Notifications show up for a few seconds and then disappear. There can be up to 5 notifications visible at any given time. When more than 5 notifications happen before the notifications start to reach their timeout, they are removed quicker to make space for new ones.

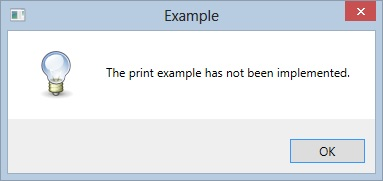

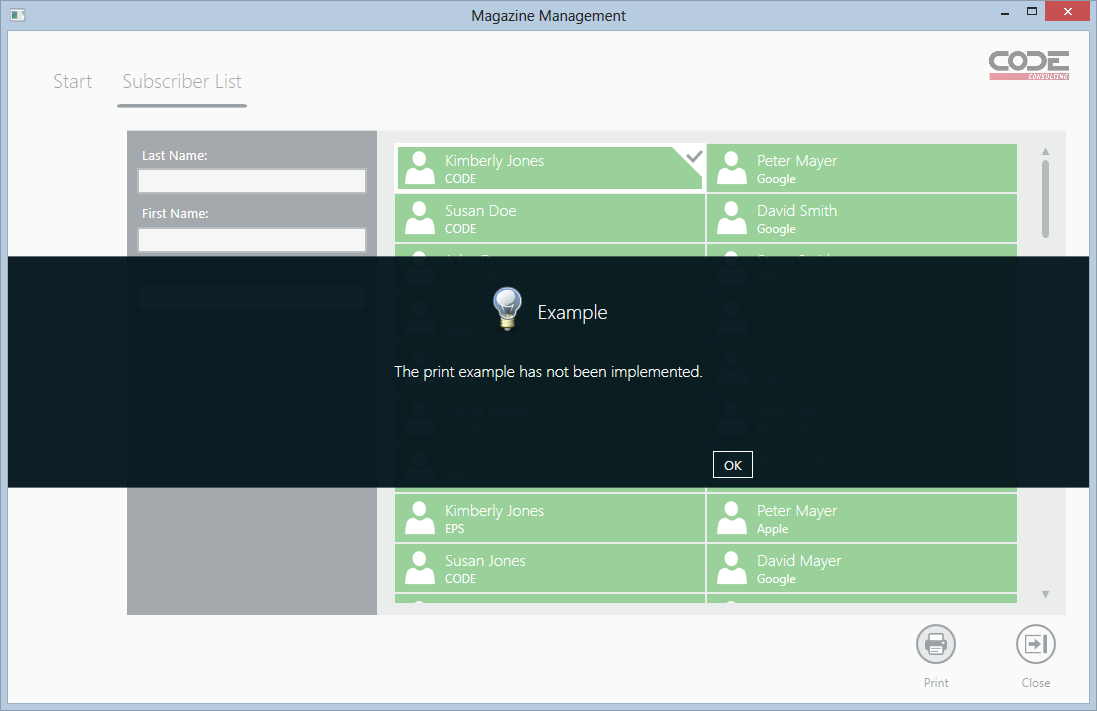

A feature somewhat similar to notifications is message boxes, except message boxes alert the user of something and need to be dismissed by clicking a button. Message boxes may of course also offer multiple choices (such as "OK/Cancel") and at times even have additional UI features (such as the ability to enter text or tick a checkbox… again, CODE Framework allows a simplified approach to message boxes as well as complete customization by passing your own views and view models into the message box system). CODE Framework features a completely A feature somewhat similar to notifications is message boxes, except message boxes alert the user of something and need to be dismissed by clicking a button. Message boxes may of course also offer multiple choices (such as "OK/Cancel") and at times even have additional UI features (such as the ability to enter text or tick a checkbox… again, CODE Framework allows a simplified approach to message boxes as well as complete customization by passing your own views and view models into the message box system). CODE Framework features a completely themeablethemeable message box engine. Figure 3 shows a simple message box in Battleship style.

Of course one of the most interesting parts is the display of actual views, such as the list of subscribers showin in Figure 1. Battleship hosts "normal" views (these are views without special attributes) inside of a tab control within the main window. The look & feel of that tab control mimics the look & feel of Internet Explorer 10’s tabs. If multiple views are open, multiple tabs are shown. Depending on which tab is selected, the menu and the toolbar changes automatically to match the selected tab.

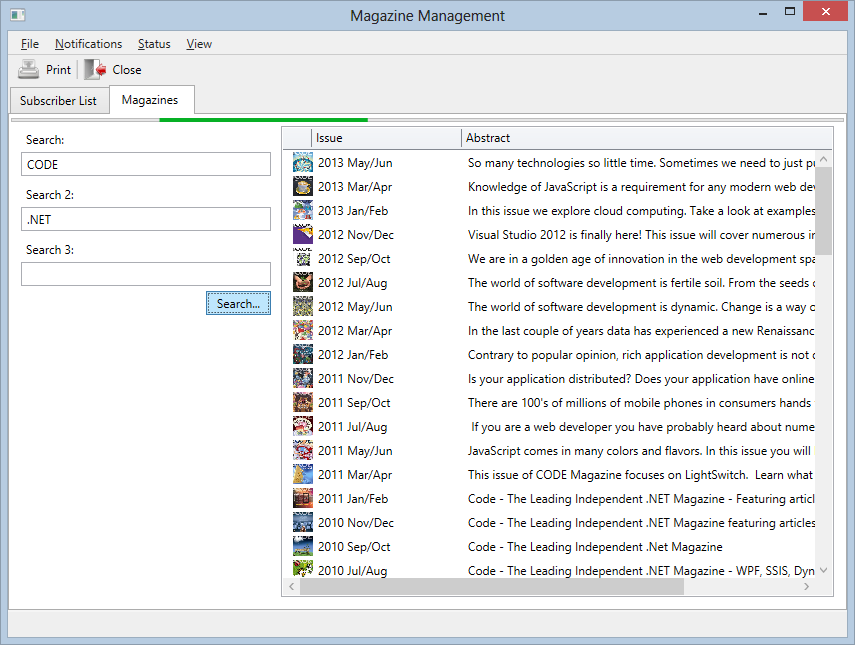

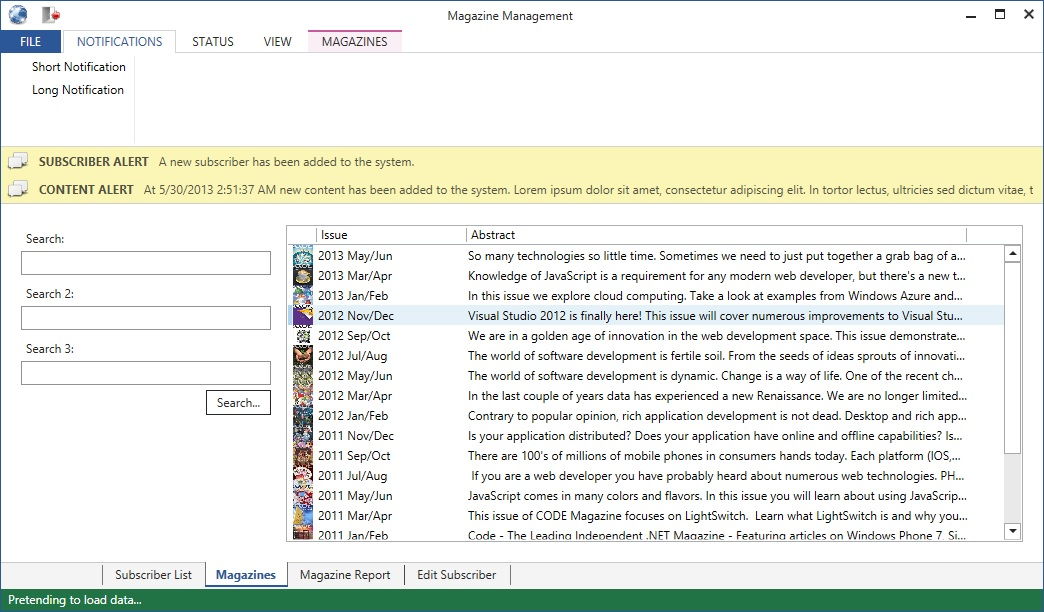

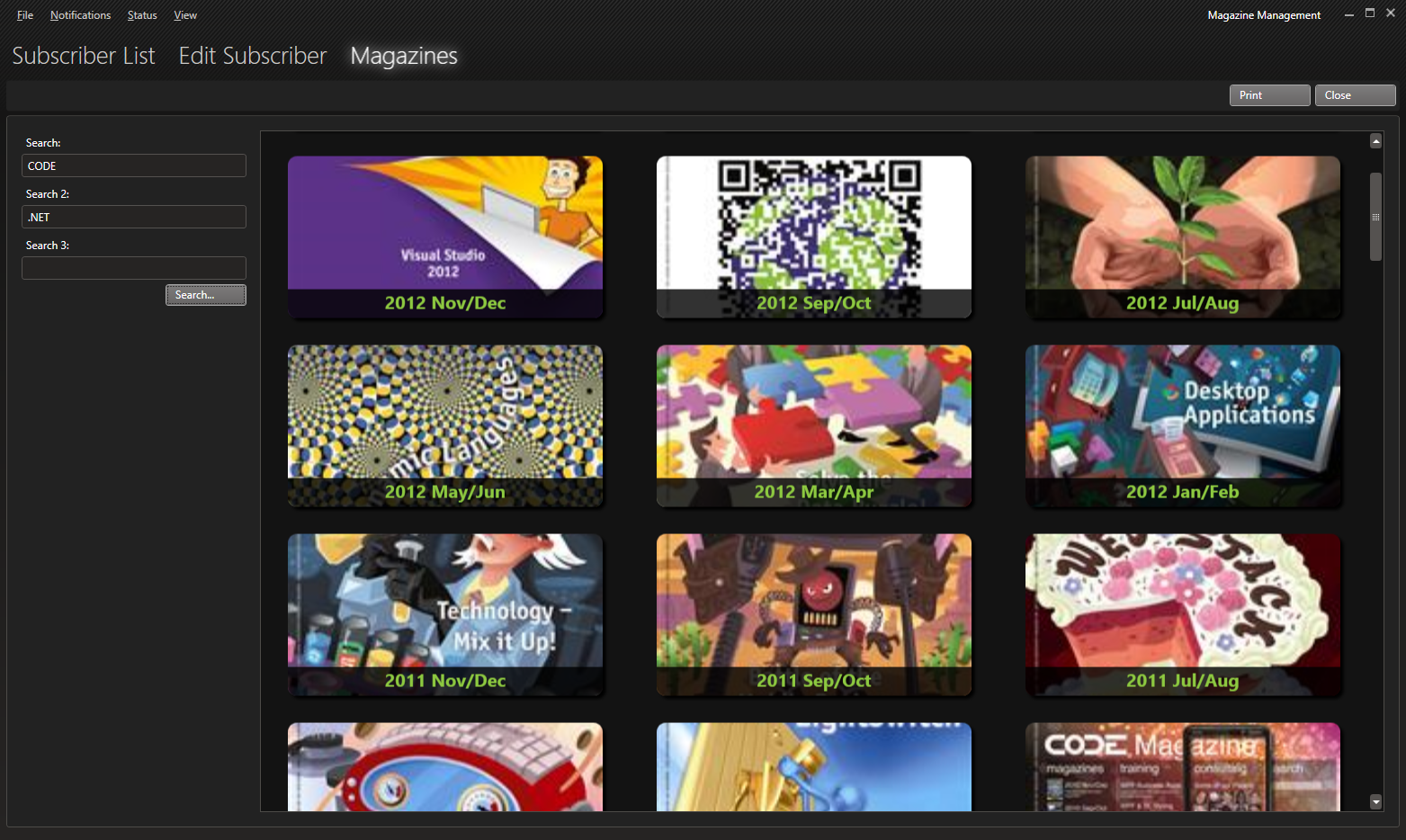

Another very interesting feature all the CODE Framework standard themes support in some fashion is automatic indication of ongoing processes. Figure 4 for instance shows a magazine search form with a green continuous progress bar at the top of the view (just under the tabs). This animated progress bar is shown automatically when the view model indicates a busy state.

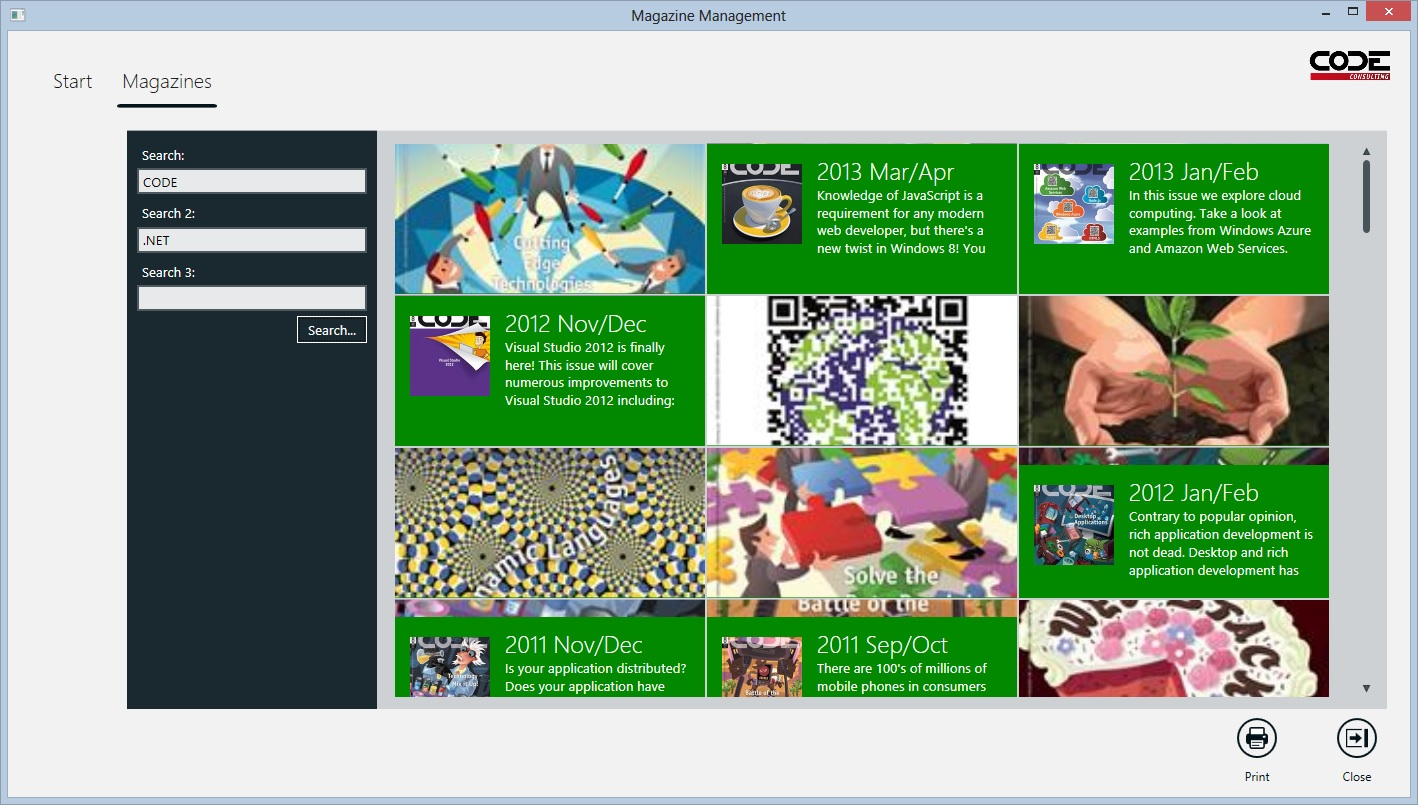

It is also worth noting that both Figure 1 and Figure 4 are taking advantage of automatic layout features powered by the theme. Both views are so-called "primary/secondary" UIs. The primary part of both UIs is the list of data and the secondary UI is the part on the left with the search terms. The list of search terms is yet another UI that uses automated layout through a "simple form" style. It is up to each theme to present these concepts differently. Battleship typically puts secondary UIs on the left side and assigned the remaining space (the majority of the space) to the primary UI (the list in this case). For "simple forms", Battleship creates a top-to-bottom bidirectional stack. Note however that this provides a result vastly superior to using a native WPF stack panel (note for instance, that the theme was smart enough to add a little more vertical space before each label than after the label). Of course all this can be customized to your heart’s content.

Using these layout features, while completely optional, offers the great advantage of being flexible, easy and fast to do, and adjusting itself automatically with themes. Here’s the code it took to create the interface shown in Figure 4:

<mvvm:View xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation" xmlns:mvvm="clr-namespace:CODE.Framework.Wpf.Mvvm;assembly=CODE.Framework.Wpf.Mvvm" xmlns:c="clr-namespace:CODE.Framework.Wpf.Controls;assembly=CODE.Framework.Wpf"

Title="Magazines"

Style="{DynamicResource CODE.Framework-Layout-ListPrimarySecondaryFormLayout}">

<ListBox ItemsSource="{Binding Issues}"

Style="{DynamicResource Issue-List}"

c:ListBoxEx.Command="{Binding EditMagazine}"

mvvm:View.UIElementType="Primary"/>

<mvvm:View UIElementType="Secondary" Style="{DynamicResource CODE.Framework-Layout-SimpleFormLayout}">

<Label>Search:</Label>

<TextBox Text="{Binding SearchText}" />

<Label>Search 2:</Label>

<TextBox Text="{Binding SearchText2}" />

<Label>Search 3:</Label>

<TextBox Text="{Binding SearchText3}" />

<Button HorizontalAlignment="Right"

Content="Search..."

Command="{Binding Search}" />

</mvvm:View>

</mvvm:View>

Hard to believe that that’s all, isn’t it?

Well, there is one more detail to mention here, actually: Part of the theming engine is the ability to display lists of data in various ways. In the example shown in Figure 4, the list of magazines is themes in the view’s Battleship resource file (example shown in Figure 4, the list of magazines is themes in the view’s Battleship resource file (Issues.Battleship.xamlIssues.Battleship.xaml) to use a standard multi-column layout:

<Style x:Key="Issue-List" TargetType="ListBox" BasedOn="{StaticResource {x:Type ListBox}}">

<Setter Property="ItemTemplate" Value="{DynamicResource CODE.Framework-StandardTemplate-DataSmall03}" />

<Setter Property="Controls:ListEx.Columns">

<Setter.Value>

<Controls:ListColumnsCollection>

<Controls:ListColumn Width="30" IsResizable="False" BindingPath="Image1" />

<Controls:ListColumn Width="150" IsResizable="True" BindingPath="Text1" Header="Issue" />

<Controls:ListColumn Width="500" IsResizable="True" BindingPath="Text2" Header="Abstract" />

</Controls:ListColumnsCollection>

</Setter.Value>

</Setter>

</Style>

This does two things: First, it tells the system to use the "DataSmall03" standard data template to present items in the list. (There is an extensive list of standard templates each theme supports, which often saves you the trouble of creating your own). In this particular case, the data template is a special template that supports multiple columns. Just using that template will create default columns. Usually, it is desirable to provide a bit more data about those columns to fine-tune their appearance. In this example, I set the width and caption of the columns as well as whether they are resizable or not. There, now we really know all the details that go into the UI in Figure 4!

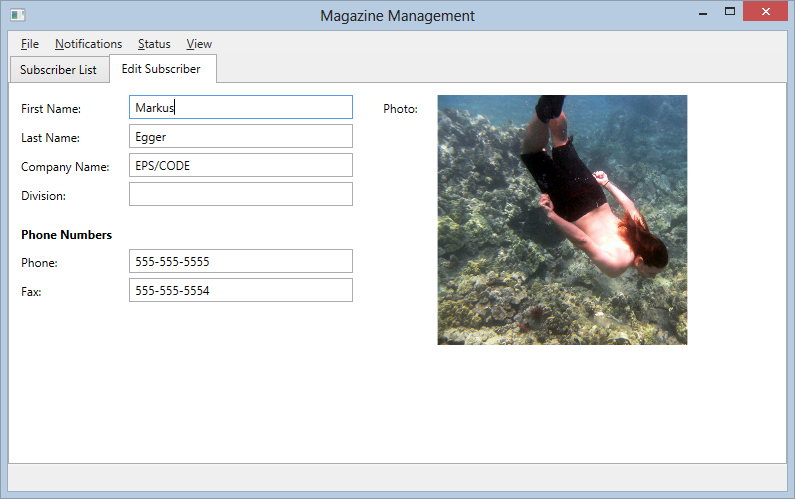

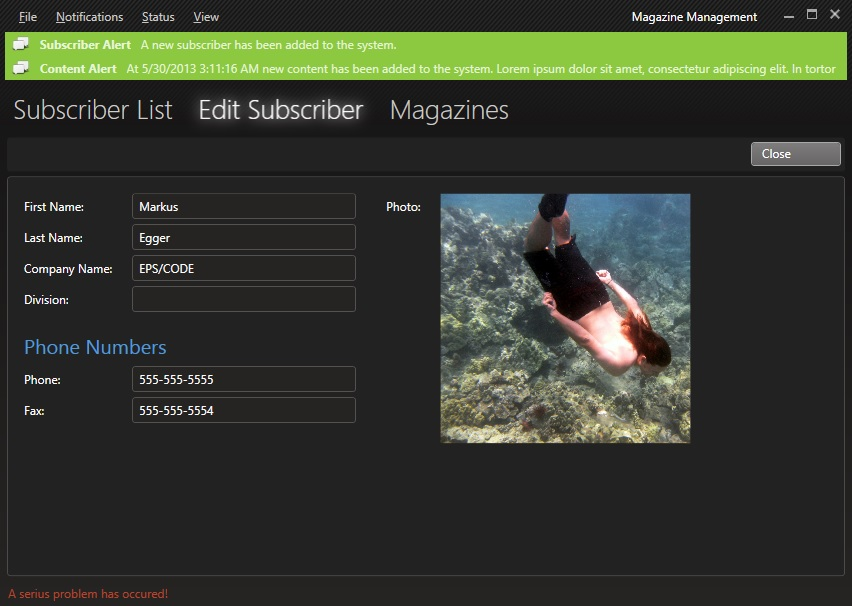

Figure 5 shows a related example. This time, the view uses an "edit form" style, which is one of the other automatic layout styles each theme supports. If you are a current CODE Framework developer, you already know how this works. Simply stick a bunch of labels and controls into a styled container (such as a view) and let the layout engine handle the layout of each control without having to worry about the details. (This is available for complete forms as well as sub-sections of forms). Figure 5 is a relatively simple example of the system (see some of our other articles for a more complete overview), yet it exposes some very sophisticated features not immediately obvious from the screen shot. For instance, the layout will automatically shrink spacing between controls and even re-flow controls when the screen is resized.

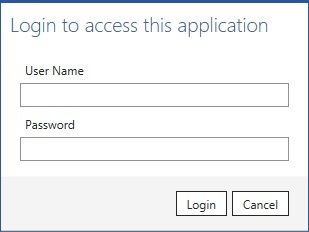

I should point out that views in CODE Framework can run at different "levels". "Normal" views are loaded into the main screen’s tab control as shown in Figures 1, 4, and 5. However, views can be given further attributes, such as being "top-level" or "modal". The Battleship theme loads top level views into their own windows. The login dialog (Figure 6) is a good example of a top level window. You can load UIs of any complexity into top-level windows. If the view defines standard actions, the Battleship theme shows those actions as a row of buttons across the bottom of the window (such as the "Login" and "Cancel" buttons in Figure 6).

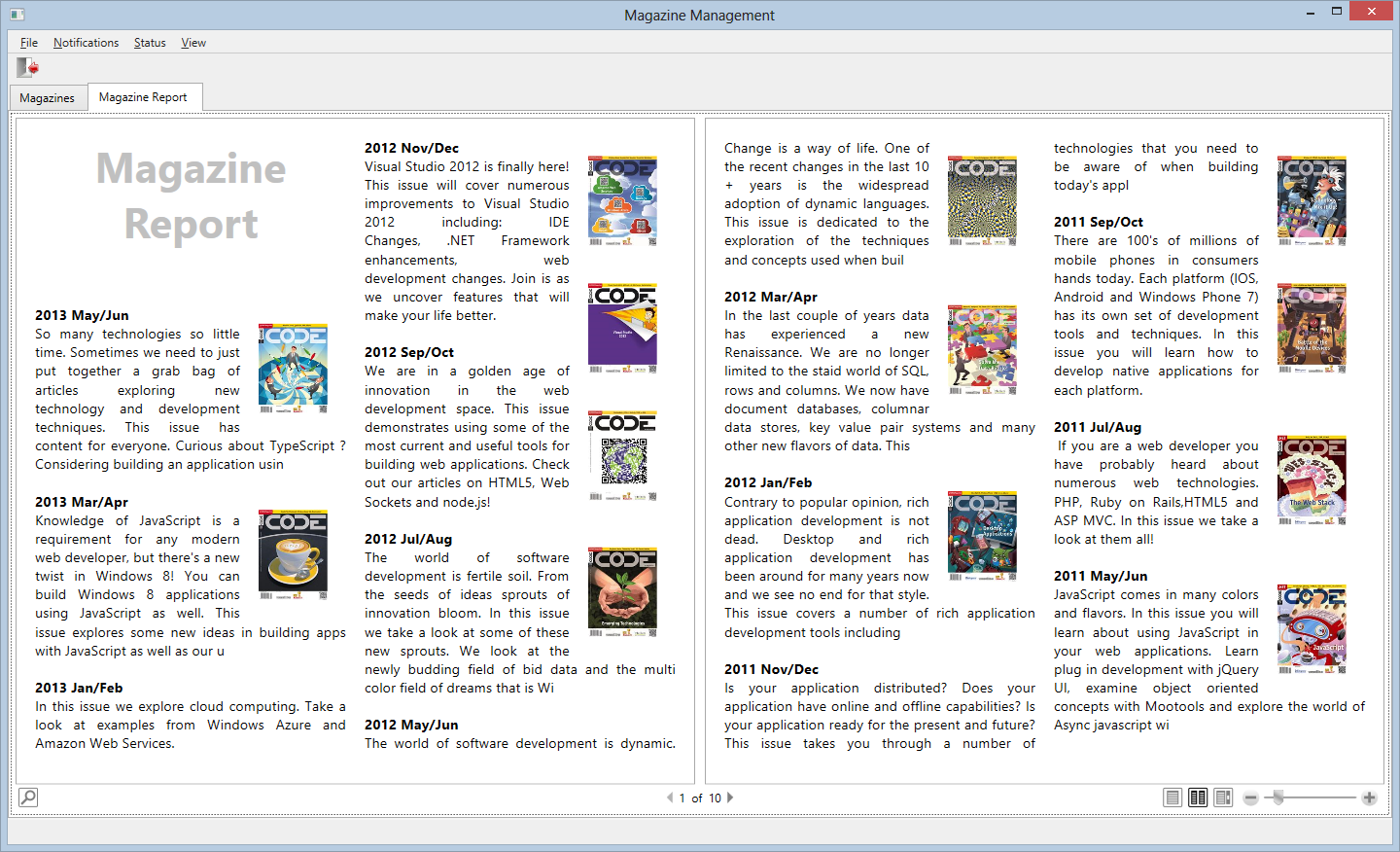

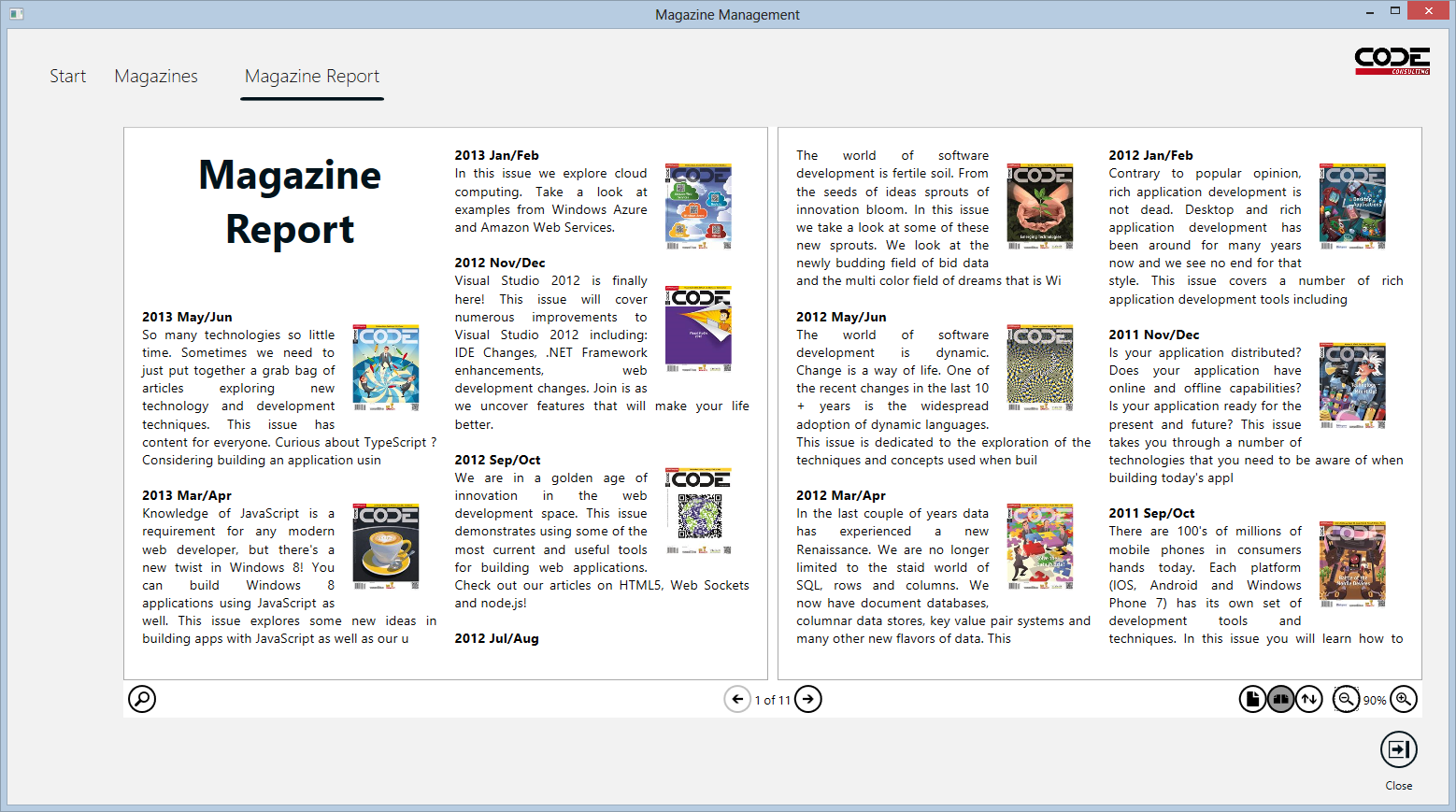

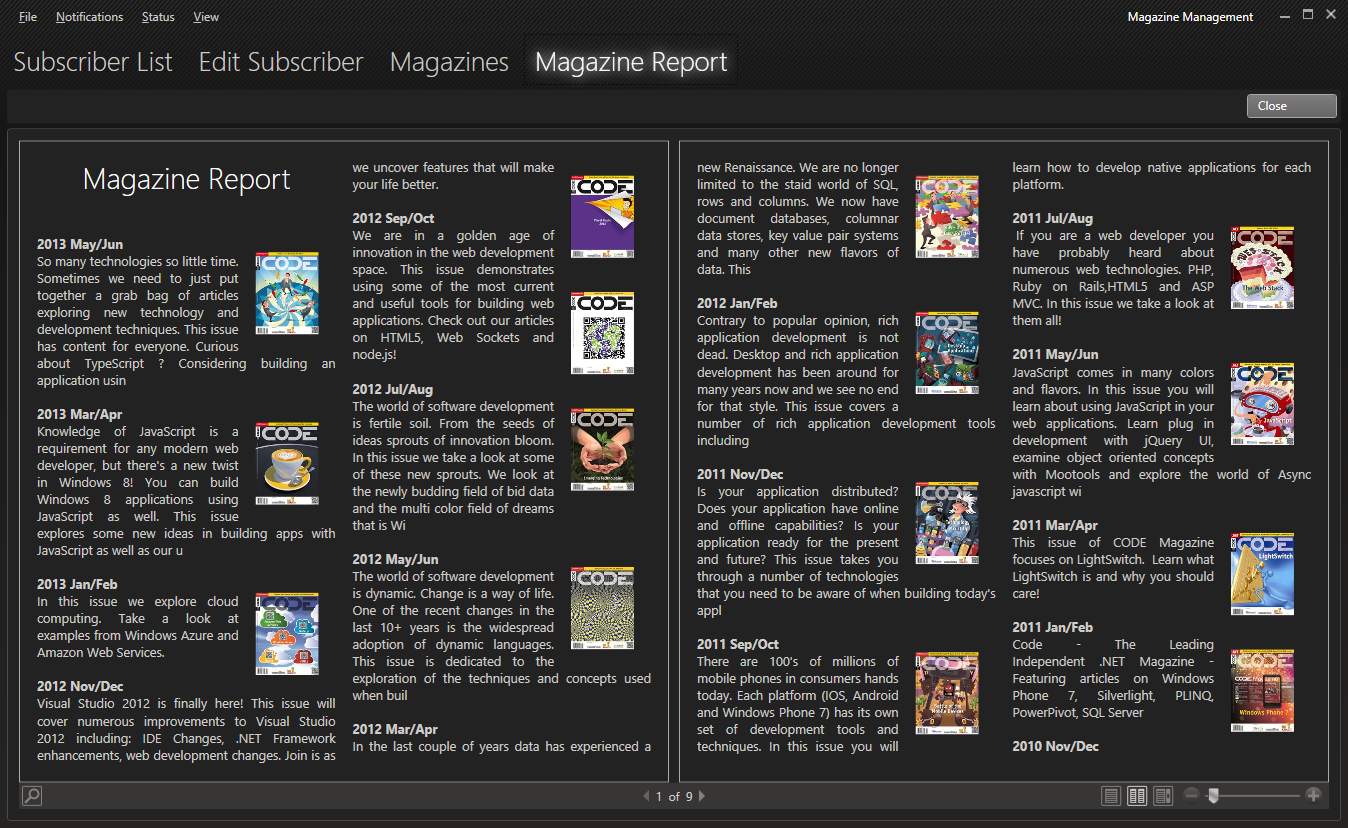

One final feature to mention is that all themes in CODE Framework support printing. Figure 7 shows a print preview of a fancily laid out magazine issue report.

Metro

Now that we have seen some of the most important features a theme provides, let’s switch things up a bit and move on to the "Metro" theme, either by going into the View menu or by shutting the application down and changing the Theme setting to "Metro" in Now that we have seen some of the most important features a theme provides, let’s switch things up a bit and move on to the "Metro" theme, either by going into the View menu or by shutting the application down and changing the Theme setting to "Metro" in App.xamlApp.xaml.

Many CODE Framework users know the Metro theme, because it is one of the first themes we shipped out of the box and it has been very popular, since it allows creating apps that look like the new Windows 8 Store apps. (And yes, we are still calling our theme "Metro", because after all, we all know that’s what it really Many CODE Framework users know the Metro theme, because it is one of the first themes we shipped out of the box and it has been very popular, since it allows creating apps that look like the new Windows 8 Store apps. (And yes, we are still calling our theme "Metro", because after all, we all know that’s what it really is is ). It is however very important to realize that CODE Framework’s WPF Metro theme should not be confused with true Windows Store Apps that run on top of WinRT. The WPF Metro theme we provide runs on all flavors of Windows that run WPF. In fact, that has been one of the great draws to our Metro theme: Create a standard Windows app that looks and behaves like Windows yet runs on older versions of Windows. (Note: To add to the confusion, there also is a CODE Framework flavor that runs on WinRT, but that is a completely different topic altogether).

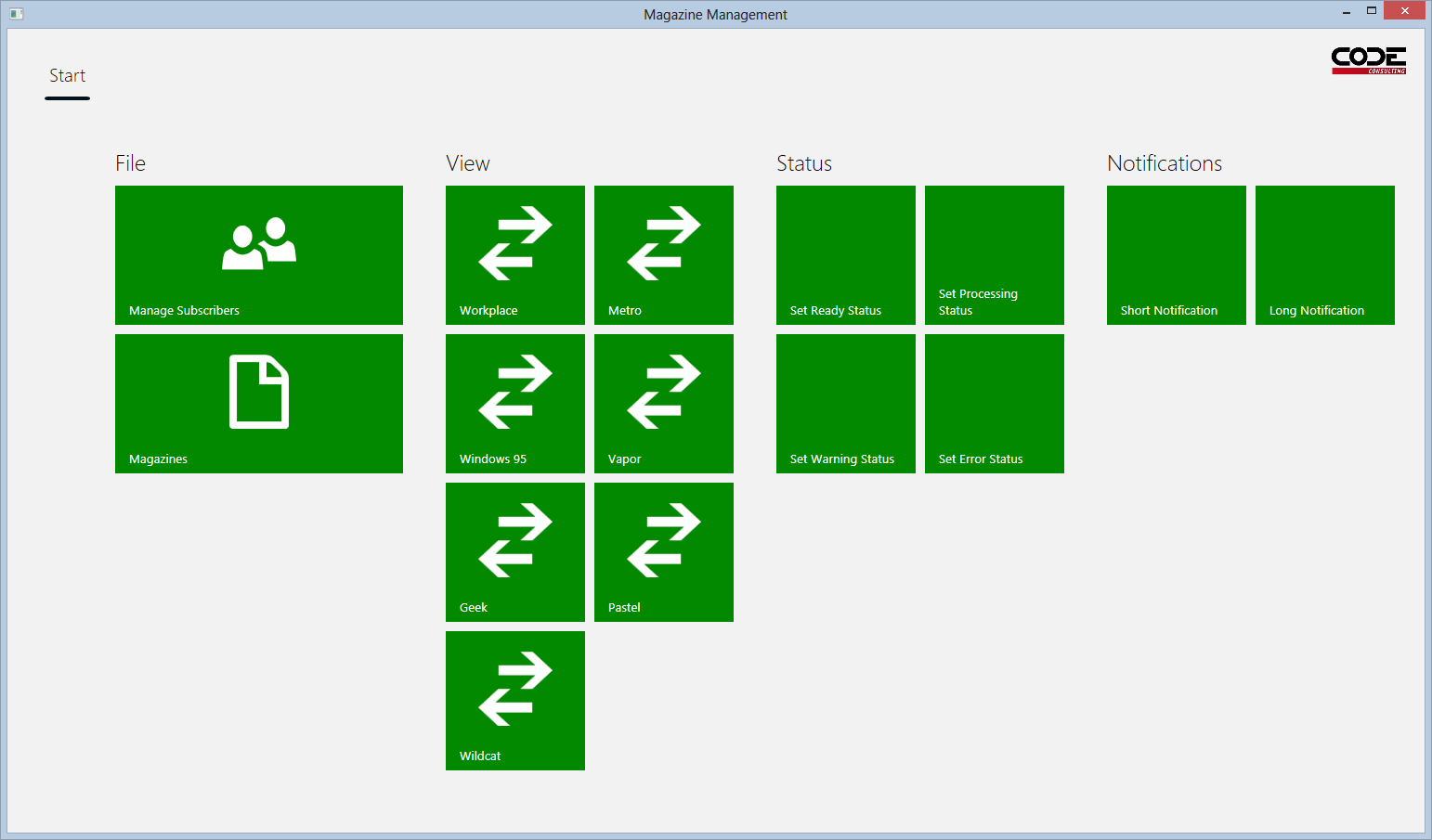

When you switch to Metro and start the app, you first see a start screen that shows all the available global actions (Figure 8). Metro applications do not feature a conventional menu, which makes them very touch friendly. (Note: Our Metro theme still supports keyboard friendly features such as hotkeys and key combinations assigned to view actions). The actual colors and background image and so forth are completely customizable through a provided color resource dictionary (this is very heavily used in Metro, but it is available in all themes). In the example in Figure 8, I chose the same color theme as the Windows 8 Store application.

Note that most of the tiles shown in Figure 8 have icons. Icons can optionally be assigned to view actions as "brush resources". If you are following along with this example and are running the app on your machine, take a close look at the icons shown in the Metro start screen. They are the typical monochrome icons seen in most WinRT applications. If you are running the app in Battleship however, the individual items in the menu or the toolbar have different icons. That’s because themes provide a list of standard icons that can be referenced by name. The standard names are always guaranteed to resolve to some useful icon resource, but they will look different in different themes (and of course you can override and supplement the list of themed icons).

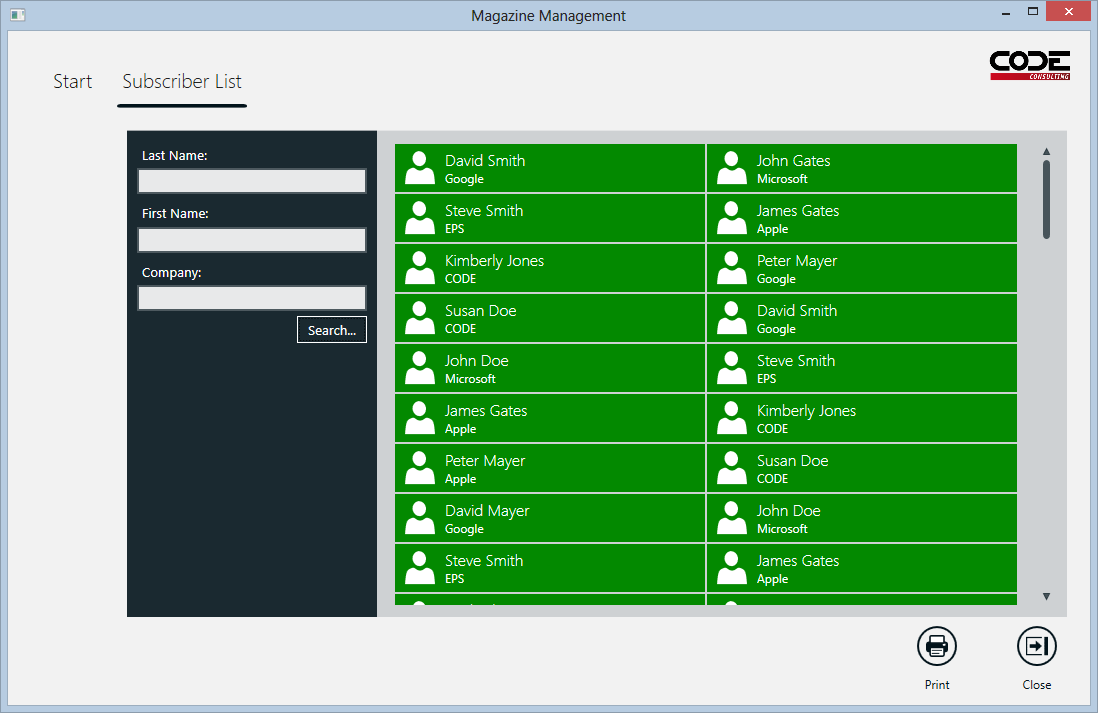

Launch into the subscriber list to see the Metro equivalent for the subscriber search form (Figure 9). While the UI is still recognizable as the same UI, it now has a Metro look. Actions that go along with the view are listed along the bottom in rounded "app bar" buttons. (Although unlike in true WinRT applications, the CODE Framework Metro theme always show these buttons and no specific gesture is required to make these actions visible, which we hope removes a major annoyance factor for most users). Note that the icons in the app bar buttons (such as the printer icon) are also Metro specific and different than they were in Battleship.

One of the more obvious changes is that the list of subscribers is now shown in a tile interface in the list, rather than a multi-column grid layout. Again, this is simply a matter of using a standard template. CODE Framework supports all the standard tile sizes and templates available in Windows 8 as well as a few extra ones. (The one shown in Figure 9 is actually a smaller tile than is available in Windows 8. Often, smaller tiles work well in data-heavy apps).

Figure 10 shows the magazine search screen, which is very similar to Figure 9. However, for magazines, I am using a larger tile size with a built-in animation. The screen shot shows some tiles in different animation states (some caught in mid-action).

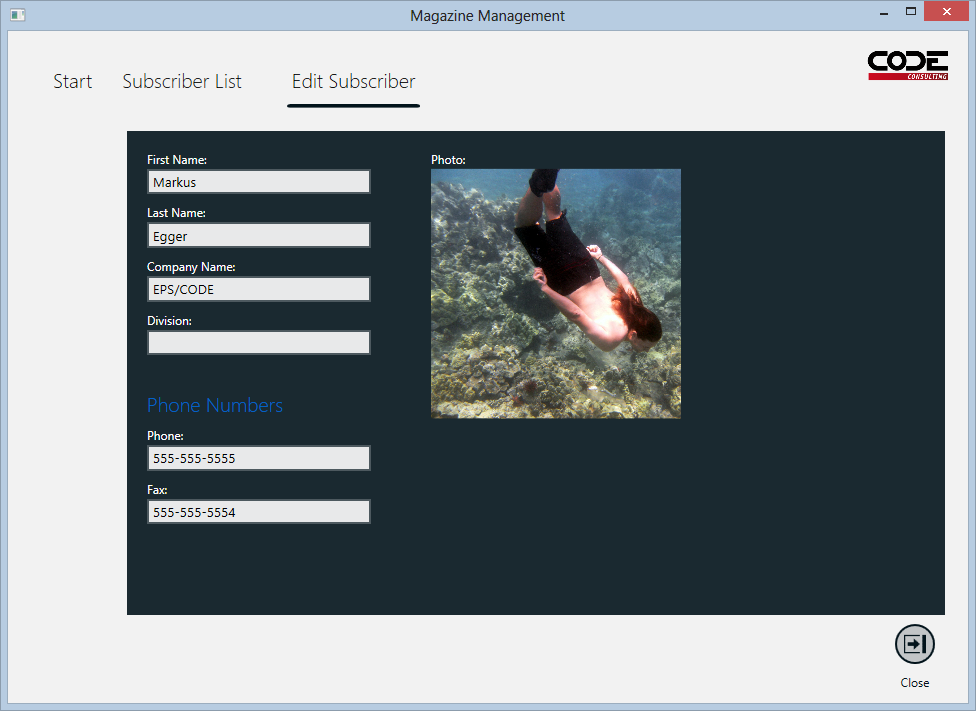

Of course Metro also supports the standard styles for automatic form layout. Single-click one of the subscriber tiles (or tap the tile if you are in a touch environment) to load the edit form (note that the theme switched to a single-click behavior for Metro, while Battleship required double-clicking). Figure 11 shows the Metro edit form. Aside from the simple blocky look of the streamlined Metro UI, you may notice several other differences. For instance, the label are now above the text controls, rather than to the left as in the Battleship theme. Of course you are free to customize all that.

As all other themes, Metro also supports notifications, status updates, and message boxes. Figure 12 shows a screen with a status message and 2 notifications. Note that status messages are displayed with different background colors (they are customizable, but defaults include red for errors, orange for warnings, and so on). The status bar in Metro is displayed only for short durations. After several seconds, the status bar fades away and will only re-appear the next time the status is updated.

In Metro, all top-level windows and message boxes are displayed in-place inside of a border that always spans the full width of the window. The height sizes to the space required. Figure 13 shows a message box using this system.

This only leaves Metro printing, which can be seen in Figure 14. Documents tend to change less with themes, although some themes may use different fonts or different sizes and colors for headings and so forth. This is especially true in preview and interactive document mode (once a document is sent to the printer, one usually doesn’t desire great differences between themes).

Workplace

What is "Workplace" you ask? Well, think about it this way: Where do a lot of people go to work? That’s right. To the Office! (Hey, we can have at least a little bit of fun with our theme names, can’t we?)

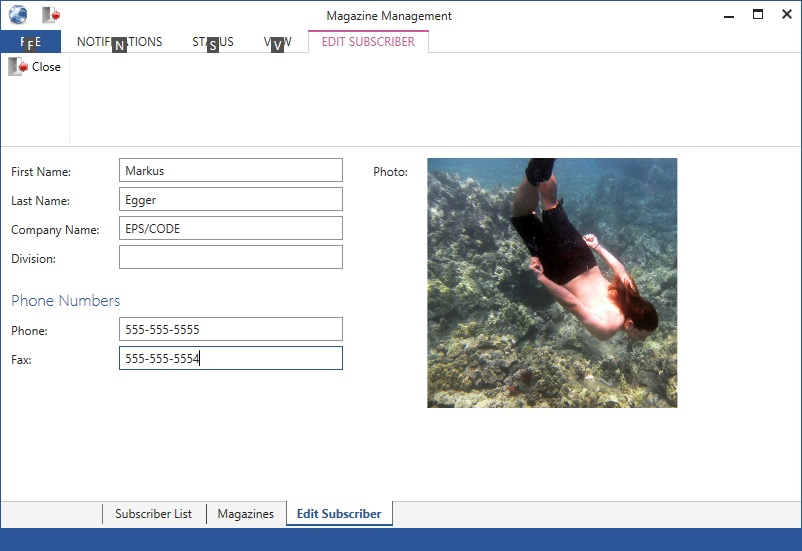

"Workplace" is the theme you want, if you want your application to look like the latest version of Microsoft Office. It uses a Ribbon approach (the Ribbon is styled in and doesn’t require custom controls). It uses the white color theme with the dark blue secondary theme color by default, but you can of course change the colors to fit your needs. In general, the Workplace theme is highly customizable. For instance, the File tab in the Ribbon usually brings up a full-screen overlay just like Office does, but you can turn that off if you don’t want that. By default, normal views are loaded into the main window with tabs across the bottom (just like Excel), but if you want, you can launch a new main window for each normal view with its own Ribbon and all (just like Word). Figure 15 shows the subscriber list using the Workplace theme.

Note that the Ribbon is highly customizable as well. If you assign custom views to your view actions, each item within the Ribbon becomes a fully customizable UI you can use any way you want. You can also set default tabs you want to show when the view first loads (actions have default properties). The significance of an action defines the size of an item in the Ribbon. If an action has its You can also set default tabs you want to show when the view first loads (actions have default properties). The significance of an action defines the size of an item in the Ribbon. If an action has its IsPinnedIsPinned property set to true, the action is pinned into the quick launch bar at the top of the window. The Ribbon supports hotkeys.

Themes don’t just switch the look of an application but also impact layout, mechanics, and behavior.

The first page File menu has some special features as well. In addition to showing the main file menu items, the special overlay takes over some of the window handling. When the file menu is open and the app launches a non-modal top-level view, that view is loaded in place into the file menu. My current example doesn’t take advantage of this, but it results in a very similar appearance to the new document dialog in Microsoft Word. In all other cases, top-level views are launched in stand-alone windows as can be seen in the login dialog example (Figure 16).

Message boxes also work like other top-level windows. Their look is very streamlined and does not feature an icon (Figure 17).

Workplace uses a similar approach as Battleship when it comes to showing primary/secondary forms as well as lists of data, with the main difference being that fonts and control details have been modified to match the Office look. Edit forms use a very clean and streamlined approach, but the fundamental layout is similar to Battleship (Figure 18).

Needless to say the Workplace theme also supports notifications and status updates (Figure 19). Notifications are displayed in a bar just below the Ribbon. Workplace apps always have a status bar, which changes color depending on the type of status update (Figure 19 shows a "progress" status).

Printing and interactive documents are pretty straightforward in Workplace (Figure 20). Note that due to the overall nature of Office-style applications, all features that are very document oriented are a very natural fit. For more information on this take a look at the article in this series that focuses on the CODE Framework document features. Many of the examples in that article use the Workplace theme.

Vapor

Vapor?!? As in "Vapor-Ware"? Who in their right mind would give such a name to a feature of their software? Well, we do. And no, this is not vapor-ware. This theme is now fully supported as a standard CODE Framework feature, although it originally started out as a small sample we used in training classes to teach theme creation. (The original theme was an homage to Valve Software’s Steam service we are big fans of. Hence the name "Vapor").

The Vapor theme serves two main purposes: 1) it satisfies the need for a black theme, since people have requested such themes a lot (with apps such as Blend or Office featuring dark themes), and 2) it serves as a great basis for further customization. You would be surprised how much you can squeeze out of the Vapor theme by changing colors and by making a few additional modifications.

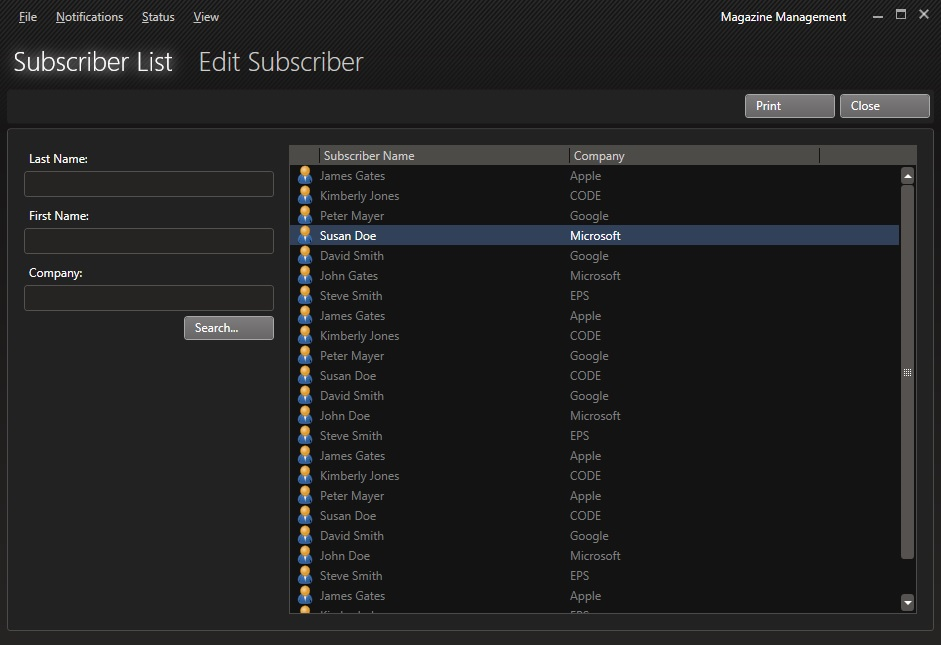

Vapor is a theme that fundamentally uses a menu, in-place activated views with a highly stylized tab control as the host. Top level windows open as new windows. Figure 21 shows the subscriber list. Note that the open UIs are listed in large letters across the top with the active one "glowing" ("Subscriber List" in this example… "Edit Subscriber" can be clicked to switch to that view). The menu works just like in Battleship. The toolbar shows all local actions regardless of significance. Toolbar buttons never have icons in Vapor. Most controls have been tweaked for Vapor. Buttons, textboxes, and so forth, all look slightly different in this theme.

One of the interesting aspects about Vapor is that it has a somewhat unique approach to lists. Some lists are formatted like data grids as the one in Figure 21, while others are formatted as larger, almost tile-like elements as seen in Figure 22. There is even the ability to switch the size of these templates on the fly.

Vapor takes a high intensity approach to showing notifications (Figure 23). This is mainly due to the theme colors used, so it can easily be modified to be much more subtle if that is desired. Status messages are a bit calmer. They appear only when the status changes for a short period of time. Different types of status messages appear in different foreground colors (the example in Figure 23 shows an error status message).

Top level views are always shown in their own windows. Message boxes are handled practically the same way in this theme (Figure 24) and support icons.

Vapor also fully styles printing and document features according to the Vapor color theme, resulting in a somewhat unique and pleasing document experience (Figure 25). Once a document is sent to the printer, it defaults to the standard black on white approach of course. (And as always, all these colors can be completely customized anyway).

For Geeks

If you are reading this article, chances are, you are a Geek. I know we are. And if you fall in this category, we have a special treat for you: A theme geared towards developers and power users! If you want your app to look like an IDE, in particular Visual Studio, the Geek theme is the one you want!

But wait, there is more!

This is not all. Our current internal builds already have a few more themes we are very likely to release as part of the open source build on This is not all. Our current internal builds already have a few more themes we are very likely to release as part of the open source build on CodeplexCodeplex soon. There is one theme we are working on that features a Ribbon and some nice color schemes. It’s made for people who like the Ribbon feature but don’t like the minimalistic approach the latest version of Office takes. Without giving away too much, that new theme will be an intricately crafted theme that combines a modern look with the detail of old-fashioned and highly sophisticated desktop apps.

Yet another theme we are working on is inspired by a popular WPF theme that was shown in many examples several years ago and has served many WPF developers as their guide for creating WPF apps without hiring a graphics artists. We are working out the details with the original creator of that theme to make sure we are not stepping on any toes, but keep your fingers crossed for a public release of that theme in the near future.

And then of course there are all the features we weren’t able to talk about in the scope of this article. And of course there is the ability to completely customize all these themes to your heart’s content. After all, you have all the source code (we even break out the theme resources into a separate ZIP file you can download from And then of course there are all the features we weren’t able to talk about in the scope of this article. And of course there is the ability to completely customize all these themes to your heart’s content. After all, you have all the source code (we even break out the theme resources into a separate ZIP file you can download from CodeplexCodeplex, so you do not have to dig through the entire code base to find them).

Take a look back through the screen shots of this article and the journey we have taken. From the battleship gray days of Windows 8 through Metro and touch-optimized UIs to modern Office apps and beyond. All without changing a single line of source in our sample application! (Not to mention that there was extremely little code in the sample app to begin with, as we were able to offload a lot of effort to the theme engine).

When I look at how sophisticated these types of applications are, yet how easy they are to build, I often wonder why there aren’t more apps with this degree of flexibility. Why can’t Outlook just switch into Metro mode and work well for touch, yet switch back into a rich desktop version when I sit in front of my monitor with mouse and keyboard? Why can’t Visual Studio look more like Office when managers or domain analysts have to use it, yet switch to the Visual Studio we know and love when developers dig in? Wasn’t all this flexibility and ease of the development the original promise of WPF anyway? Yes it was! Hopefully, I was able to show the way to unlocking some of that power.